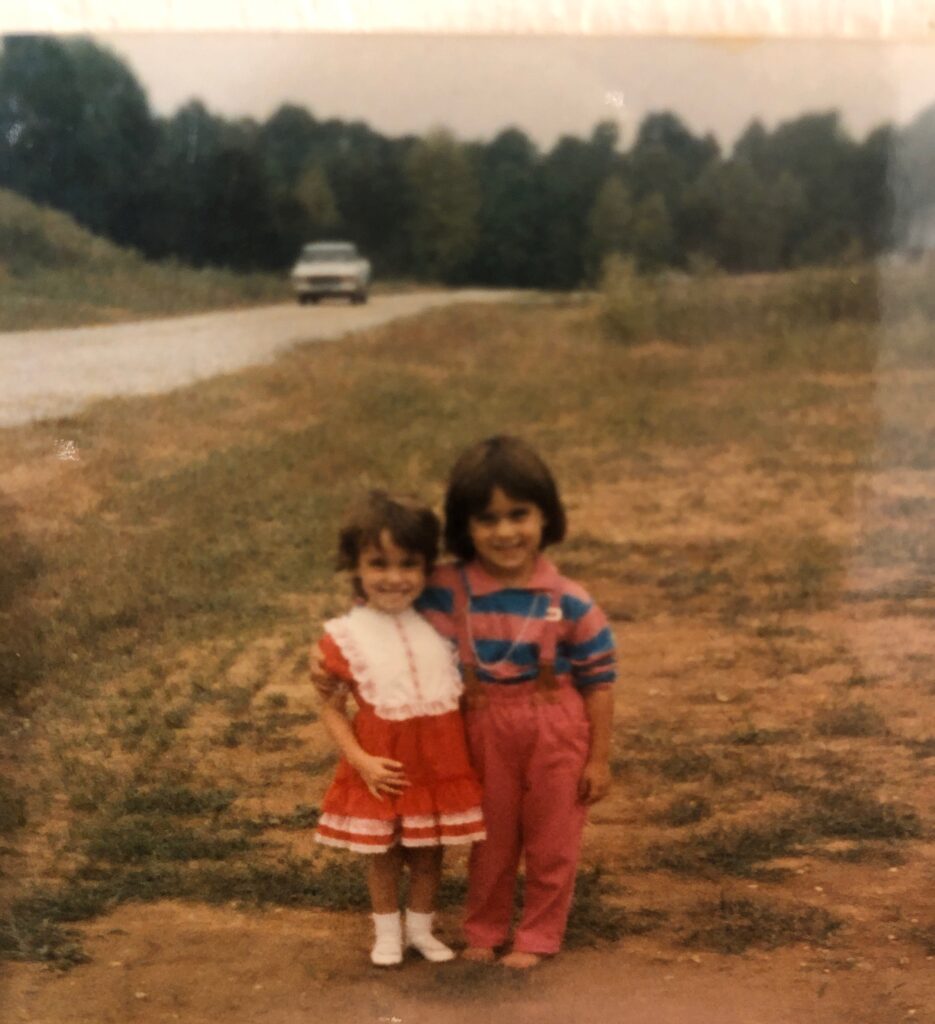

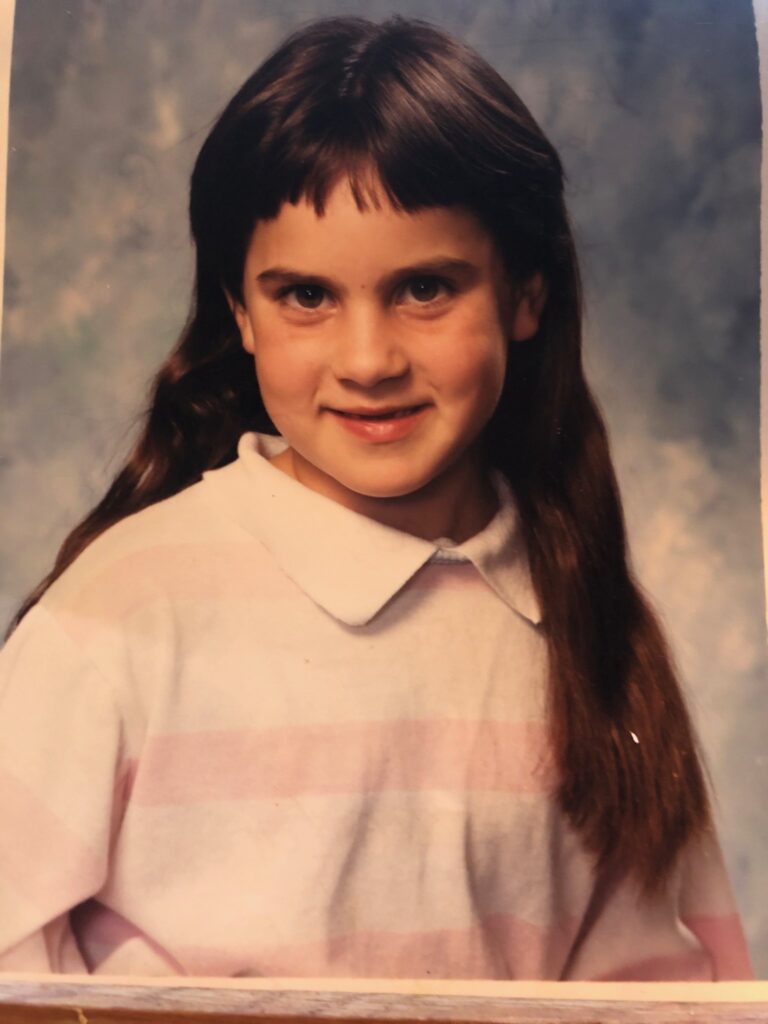

When Lindsay and I were in our mid-20s, we still lived in the community where we grew up. One of the things I loved most about growing up in Southeastern Pennsylvania was a decades-long stability of place that created a deep sense of belonging. I loved my intimate familiarity with the ecosystem, the regular and predictable cadence of the seasons, and I loved being a part of a community that had known me forever.

One of the examples where this last feature was most readily observed was in the church where I had grown up since I was two years old. By the time I was 25, I was a card-carrying Green Party member and I didn’t believe most of the fundamental teachings commonly accepted in Christianity (i.e. the existence of a God, the reality of an afterlife, etc…). Nevertheless, I still attended the small, community church regularly. Lindsay asked me why I kept going when my beliefs were so dissonant with the institution’s. “I like the potlucks,” I said. “Plus, where else am I going to see Donna and Brian? Or Tom? Or Lynn? I love seeing those people.” And thus, I continued to go.

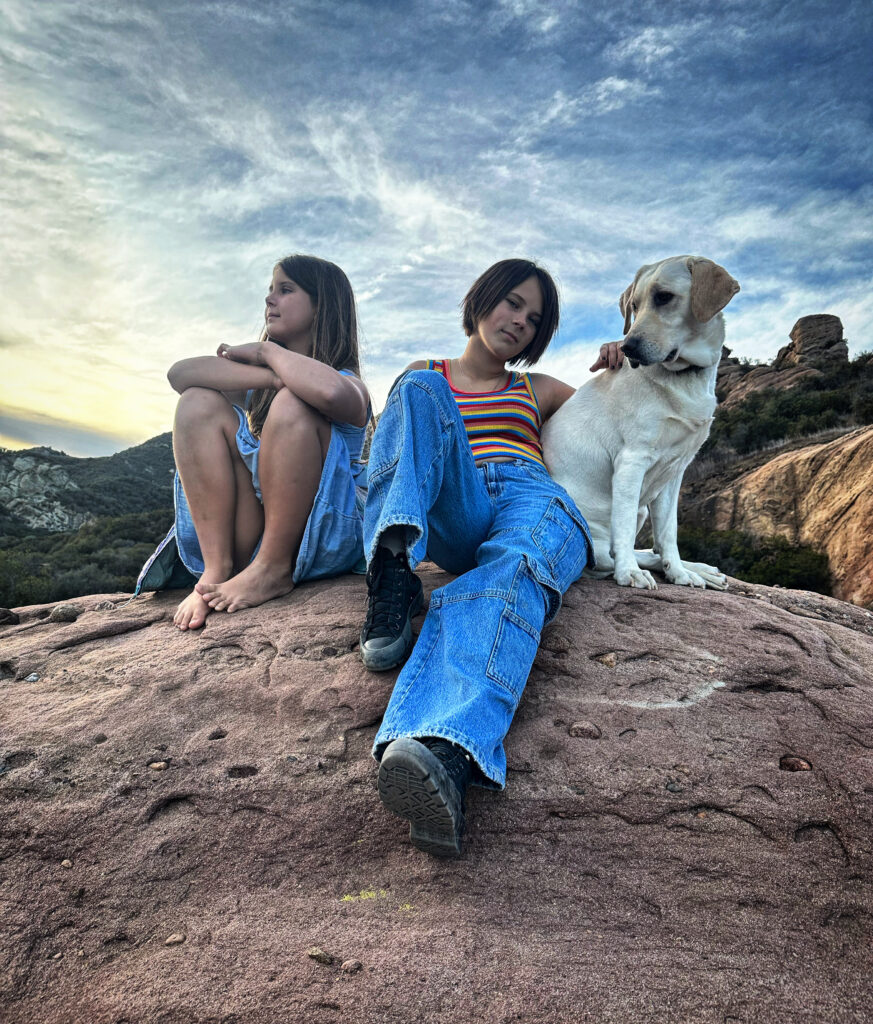

Over the past decade and a half, our family has moved several times. We’ve made big moves across the country and, while we have sought to maintain consistency in practices that reflect and support our most deeply held values, we have fully abandoned the practice of attending any form of religious community. This has been a notable departure from our upbringing. Growing up, church was where we found friends, community, and a sense of belonging. Church is designed to address the core psychological needs for explanations, belonging, stability, and community.

Across all of these moves, it has been important for me to maintain a close connection and warm relationship with the people I hold most dear from the early part of our lives. I love my family and friends and I don’t want to grow apart from them or lose touch with them. It’s a common thing for people to grow apart with distance. It’s even more common for people to grow apart after experiencing large shifts in belief and the systems that support them.

I’ve spent significant time thinking deeply about what I still share with the important people in my life who have not taken this same path. I have done a lot of reading about what binds people together despite differences in belief systems. Here’s what I think lies at the core: Shared Values.

Throughout my exploration of the importance of core values, it has been helpful for me to distinguish between values and beliefs. Both are fundamental components of our worldview and decision-making processes, but they serve different purposes and influence our behavior in distinct ways.

Values are core principles or standards that guide what is important or beneficial to an individual. They are deeply ingrained and stable over time. They are emotional and evaluative. Some examples of a value might be, “Honesty is important to me” or “I value kindness and compassion.” Values are usually instilled by your family, culture, and/or societal influences. They are established at a young age and tend to be stable over time. While they can evolve over a lifespan, a change in core values usually requires a lot of new life experience and thoughtful work. Values serve as a compass for behavior and a guide for how we interact with others and make decisions. Values often underpin our goals and aspirations.

A belief, on the other hand, is an acceptance that something is true or exists, often without proof. Beliefs can be about facts, opinions, or perceptions. Beliefs are cognitive and can be based on knowledge, assumptions, or faith. For example, to express a belief, one may say, “I believe that hard work leads to success,” or “I believe that there is a God who loves me.” Beliefs often point to a deeper value. For example, “I believe that it is wrong to lie” is a moral belief that points to the value of Truth. Beliefs are formed through personal experiences, cultural influences, education, and social interactions. Beliefs change with life experiences and the assimilation of new information. Beliefs help us interpret and understand the world around us in real-time.

Simply put, values are the deep stuff. They define who you are. Beliefs are about what we think is true, but values are about what we think is important.

THIS is why a non-religious liberal still loved the church potlucks. Tom and I would talk about creative solutions to complex problems because we both value Creativity and Ingenuity. Lynn and I would connect on issues of inequality because we both value Justice. Donna, Brian, and I would talk about their kids because we all value Love and Family. None of our conversations were about the origins of the universe or what happens after we die. I knew we believed differently about those things. We talked about the stuff that we all cared deeply about. It was wonderful.

When you move beyond the level of Beliefs and look for common ground on the level of Values, there’s incredible opportunity to connect with other people. It is possible to form deep and meaningful relationships with other people–even if you do not share beliefs–if you DO have shared values.

There’s a dark side here though. It’s something I have seen a lot with people of faith. When you invert the importance of values and beliefs and you place your beliefs above values, this can be deeply destructive.

On a personal level, this can destroy relationships. On a societal level, it can destroy entire people groups and cultures. This is not an exaggeration. Think of the Crusades. Think of the Holocaust. These are extreme examples of people acting out of a dedication to their beliefs in a destructive manner. The people behind these atrocities believed that they were right. In today’s world, we see this expressed in how people vote. Destructive and powerful leaders have been elected to positions of power because they purport to share a belief system with voters. I would implore you to look beyond a candidate’s stated beliefs and try to discern their values by examining their actions. Are they honest? Are they kind? Are they respectful? Do they seem wise to you? Remember we all value different things. People can value things you actually think are bad. Some people’s core values are power, control, and success over anything else. Some people think that kindness and honesty represent weakness. Placing belief systems above how values are expressed in action is a dangerous subversion that can come with horrific consequences.

On a more individual level, I’ve seen the personal impact of placing beliefs over values over and over again in my life. Growing up in the church, I have seen families grapple with this as their kids leave the nest (as well as the church and the faith). Some of these families have stayed close to their grown kids. Some haven’t. The difference? People who connect on shared values stay close whereas people who prioritize beliefs grow apart.

If you place more importance on being right or defending your beliefs than keeping a strong and warm relationship, you will lose that relationship. Guaranteed. Remember, beliefs are PERSONAL. If you try to make them objective and hold others to them, you are placing your beliefs above the value of Relationship (also this may be this is a sign that you value Authority more than you value Connection… if that’s the case you can change that with thoughtful work). If you confront someone or refuse to accept someone because you believe that their religious or spiritual view is wrong or the expression of their gender or sexuality is wrong, you are placing your own, personal beliefs above shared values. You are rejecting something deep and personal about that individual by telling them THEY are wrong. You will hurt them and drive them away.

I can think of so many times I’ve seen this happen. Invariably, the aggressor says they are acting out of love for the other person. I would challenge this though. If you place your personal beliefs as your top priority, you aren’t operating out of Love. You’re operating out of fear. Fear that the other person is wrong because they don’t share your beliefs. If you truly believe that perfect love casts out fear, I would encourage you to pause and reflect before confronting someone on a difference of belief. Rather, look for a shared value. Look for a place to create connection rather than confrontation. Look for a way to nurture rather than control.

I think that a good test for whether confrontation is a wise choice this: “Is whatever you are confronting harming or oppressing someone else?” There are times when it absolutely makes sense to confront a difference in beliefs. Most activism is designed to target outcomes that spring from a difference in beliefs. I think it’s admirable and right to stand up against oppressive belief systems like white supremacy. Even beliefs that are held with deep conviction can be deeply flawed and profoundly harmful. That’s when it makes sense to get in touch with your most deeply cherished values (for example: love, equality, justice, etc..) and confront forces that are working against those values.

Maintaining healthy relationships and activism are quite different pursuits. I do think that it’s a valuable skill to look beyond beliefs and focus on values whenever possible. It’s a tricky balance and one I’m sure I haven’t perfected.

In my 20s I rarely spoke up about the differences in my beliefs. It wasn’t because I couldn’t defend them. It was because I preferred to focus on the common ground rather than the differences. I preferred to connect rather than divide. But I was also afraid of the rejection I’d face if I was transparent about my beliefs. I saw this kind of rejection a lot. I can think of example after example from my childhood where people who were outspoken and honest about their differences in beliefs were rejected in deep ways by important people in their lives. A lot of those people are not doing well today. They lost a lot at a critical age and it left a mark.

A fundamental part of the human experience is a quest for belonging. But true belonging can only exist when we live authentically according to the stuff we think is most important. How can one belong without truly being known and how can one feel known without others understanding the deep stuff that defines you? I think this is why we all have such a reflex to assign labels; so we can easily know and be known. Each of us must confront a chasm as deep as the human heart that craves the eloquence of allegiance. What DO we stand for? Who are we, really? What do we think is most important?

But labels usually fall woefully short because they tend to focus on a tiny sliver of who we truly are. They tend to cover things related to beliefs, affiliations, views, vocations, etc… Counting people in or cutting people out based on one tiny aspect of their being is simplistic at best. True belonging can only come when we have time to share the deep stuff.

As I’ve grown older and built a life less vulnerable to losing resources due to belief-based rejection, I’ve become much more comfortable talking openly about my beliefs and my identity. You see, I’m confident in what I believe and I’m proud of what I value. I believe that Nature and all that it encompasses is beautiful and sacred. I have a deep reverence for life and all of its delicate interconnectedness. I try to cultivate wonder. I pursue awe. My heart melts for warm, kind, caring relationships. I love a supportive community. I marvel at the power that Love has to nurture, restore, and create beauty in the everyday.

You see? That’s a lot of room for common ground. We may have different beliefs about origins and endings, but there’s a lot of great stuff in the middle where we can connect.

Hopefully someday I’ll see you at a potluck.